Support the LA Phil

Keep the music going. If you are able, please help the LA Phil continue to make programs like this one and impact lives through music education.

Give now:

Season 1 - EP9

Finales

This concert’s streaming date has passed. Enjoy its accompanying essay, interview, special performances and more below.

This episode was released on Jan 1st

About the episode

It doesn’t matter how little you know about music theory or a particular composition. When a finale is approaching, you can feel it. Whether an orchestral piece concludes with a bang or a whimper, its ending is rarely ambiguous. Other art forms differ, as does life, in which endings are often just beginnings to something else entirely. There’s only one thing a final movement, third act, and proper goodbye will always have in common – they are never easy to get right.

Gustavo Dudamel

Conductor

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Orchestra

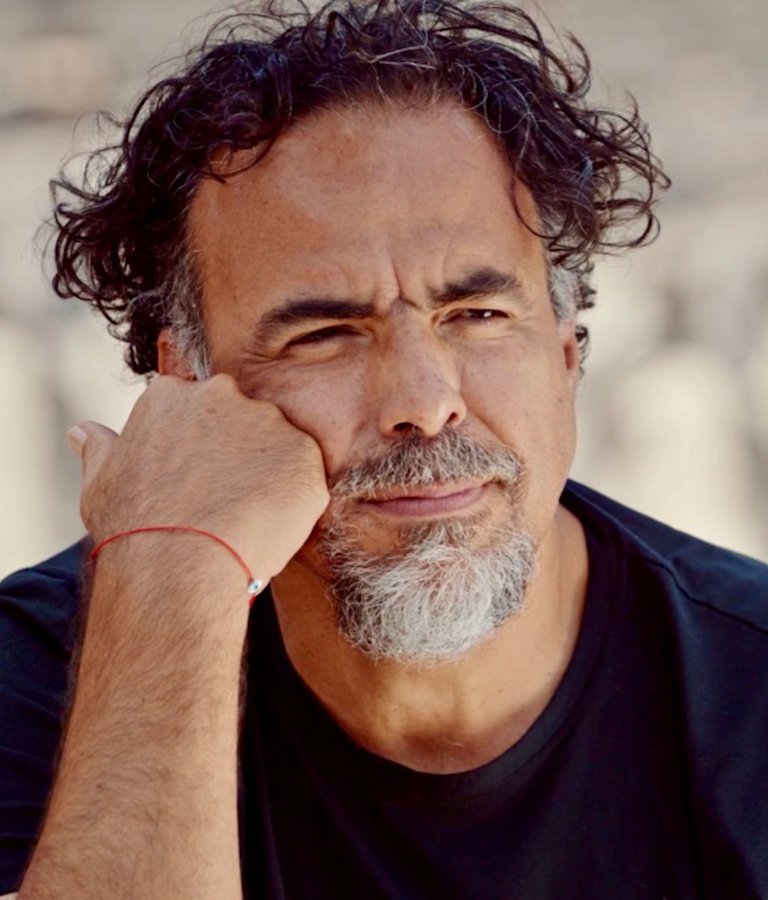

ALEJANDRO G. IÑÁRRITU

Special guest

Program

Mother Goose: “The Fairy Garden”

Born in southern France in 1875, Maurice Ravel was a perfectionist who believed that every musical problem had an ideal solution. He often composed pieces for the piano that he then orchestrated, becoming one of the greatest orchestrators who ever lived. He originally composed Ma mère l’Oye (Mother Goose) as a piano duet for the children of friends; the subtitle is “five children’s pieces.” To conclude his magical suite, “The Fairy Garden” begins very softly with a stately, inward feel that gradually becomes more noble and then soaring, in colors so gorgeous that we might wish we could stay in the Fairy Garden forever.

Composed: 1911

Orchestration: 5 first violin, 5 second violin, 4 viola, 3 cello, 2 bass, 2 flute, oboe, English horn, 2 clarinet, 2 bassoon, 2 horn, percussion, timpani, harp, celesta

Symphony No. 7: IV. Allegro con brio

Despite his deafness, Beethoven conducted the 1813 premiere of his Seventh Symphony at a concert that became one of his most successful, partly because his orchestra included some of the greatest musicians of the age. Richard Wagner later wrote, “The Symphony is the Apotheosis of the Dance itself.” That phrase continues to be repeated because it’s so apt; more than the harmonies or melodies, it’s the dance rhythms that draw us in. The astonishing fourth-movement finale zips along with Bacchic fury in a tour-de-force of whirling dance energy.

Composed: 1813

Orchestration: 5 first violin, 5 second violin, 4 viola, 3 cello, 2 bass, 2 flute, 2 oboe, 2 clarinet, 2 bassoon, 2 horn, 2 trumpet, timpani

Corpórea: “Ritual Mind – Corporeous Pulse”

Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz (b. 1964) incorporates contemporary, rock, African, and Afro-Cuban influences into her compositions. Her Corporea for flute, clarinet, horn, trumpet, percussion, harp, violin, cello, and bass describes an oscillation between our material existence and our most spiritual condition. The fourth and final movement – “Ritual Mind – Corporeous Pulse” – reflects the most rhythmic, primitive, and earthly aspects of life. Corporea is dedicated to Mexican diplomat Gilberto Bosques Saldivar (1892–1995), who risked his life to save hundreds of Jews and Spanish Republican exiles.

Composed: 2015

Orchestration: violin, cello, bass, flute, clarinet, horn, trumpet, harp, percussion

Endings

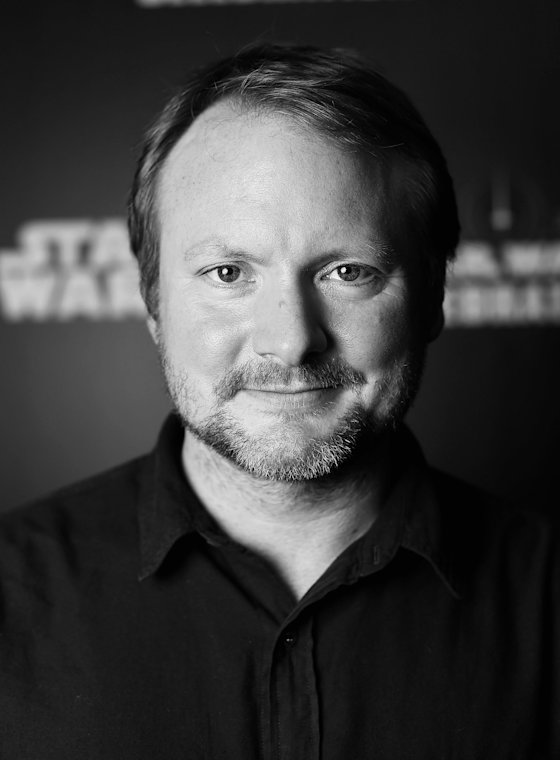

by Rian Johnson

I love endings. To say that I consider a good ending to be the entire point of telling a story is not far off the mark. A good ending is more than just a big bang, a fun flourish, or satisfying twist. A good ending works because it contains the entire journey within it, the beginning and the middle, the entire story concentrated and re-contextualized, loaded with gunpowder, then hopefully going “bang.” An ending works because of everything that came before it.

So what to make of a program of endings divorced from their beginnings?

Will the galloping final movement of Beethoven’s 7th have the same emotional impact if we have not been through the allegretto to get there? No… but our brains will do what they do best, and fill in the blanks. The final movement will be parsed as its own drama, we’ll each find the beginning, middle, and end within the ending, and that’s pretty damn exciting. Or even more interesting - through the program, we’ll each create our own dramatic journey between Ravel, Ortiz, and Beethoven, a musical game of exquisite corpse.

An ending works because of everything that came before it.

In that way, can a program of “endings” really even exist? Our brains are built to take disconnected information and narrativize it, create cohesion and shape, often from incomplete pictures. With the drama and power of these pieces we’ll find it impossible to hold some abstract notion of disconnected finales in our head, and we’ll each stitch our own story together. The evening will have its own beginning, middle, and end. But - and here’s the exciting thing - whatever that ending ends up being, it will be totally unique to this program, the product not of composition but of our own individual powers of storytelling.

I’ll be listening not to a series of endings but to a story that will exist just this once, and will end, hopefully, with a “bang."

Author Bio - Academy Award and Golden Globe-nominated filmmaker Rian Johnson is known for crafting films with their own artfully designed voice and look, and for telling unique stories that blend the pulp of genre with a genuine soulfulness. He recently wrote, directed, and produced the Agatha Christie-style murder mystery Knives Out (2019), for which he received Academy Award, WGA, and Critics’ Choice Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay. The film, which premiered at TIFF and grossed over $309 million at the worldwide box office, was also nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Picture – Musical or Comedy. Johnson’s previous films include Brick (2005), the Festival selections The Brothers Bloom (2008) and Looper (2012), and Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017).

In conversation with

Alejandro G. Iñárritu

Gustavo Dudamel is joined by Academy Award-winning director Alejandro González Iñárritu in a conversation about the creative process, whether an artist knows where they’re going when they begin, and the nature of endings themselves.

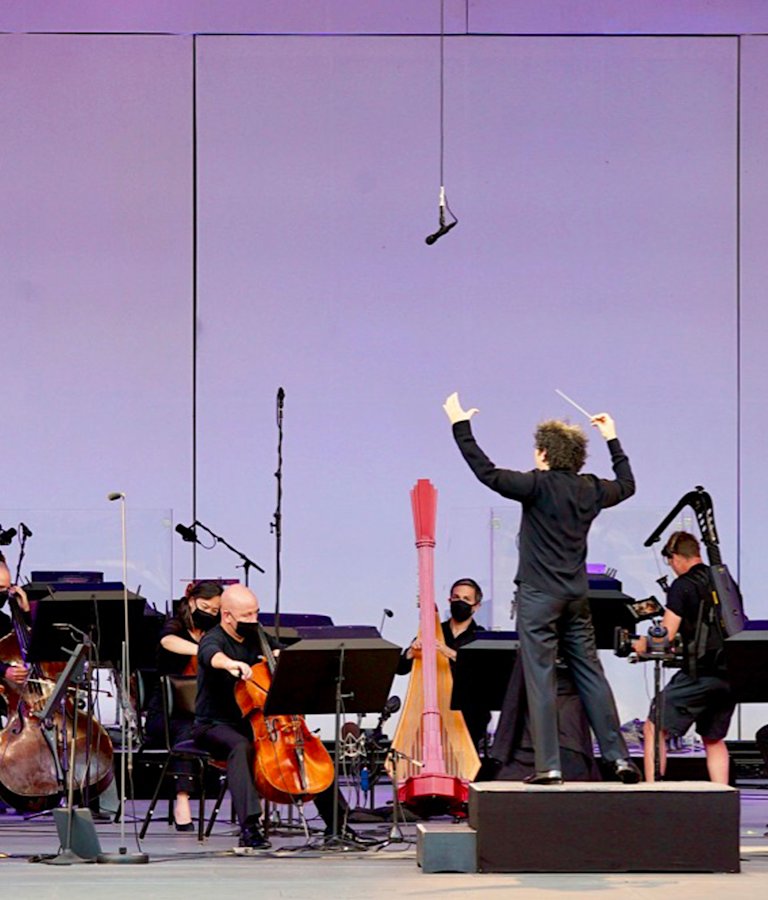

Gustavo Dudamel leads the Los Angeles Philharmonic in Beethoven's Finale, from Symphony No. 7

Assistant Principal cellist Dahae Kim playing on Ravel's Mother Goose: "The Fairy Garden"

Wesley Sumpter, Judith and Thomas L. Beckmen LA Phil Resident Fellow

Director, producer, and screenwriter Alejandro G. Iñárritu talks with Gustavo Dudamel on the nature of finales

A look behind the scenes while the crew sets up for episode 9 of SOUND/STAGE

The Bowl lights up for Gabriela Ortiz's Corpórea: “Ritual Mind – Corporeous Pulse”

Martin Chalifour, Principal Concertmaster and Robert deMaine, Principal cello

Gustavo leads members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the Gabriela Ortiz piece

Matthew Howard, Principal percussionist

Dudamel conducting a masterful finish to episode 9 of SOUND/STAGE

In conversation with

Gabriela Ortiz

LA Phil Music and Artistic Director Gustavo Dudamel joined composer and friend Gabriela Ortiz for a conversation about her work, the Pan-American music scene, and the two sides of being human.

The following has been edited for length.

We are doing this beautifully mad thing – putting together an orchestra to play and make music that moves us. You are part of our family, of the Philharmonic, and we thought of you immediately and your wonderful work Corpórea. It has a very unique energy and is so well written. Tell me about the piece.

When I write music, I am always swinging between the rational part, how we function mentally, and the irrational part – the instinct or institution, the magic part. I think you also go through this when you conduct – one part plans the rehearsal to be very productive – how you are going to distribute the time, what parts you are supposed to rehearse. But then comes the magic part – suddenly, there is intuition, suddenly you change your mind. I am always between the planning part and the intuition part. The last movement, which is the one you’ve been working on, is very rhythmic, very visceral. That’s the idea – how to get to this primitive, obsessive drive. It is playing with the pendulum between the spiritual and the visceral. Because I am Latin American, that rhythmic part is an important characteristic of my work.

Speaking of which, you are also the curator of our Pan-American festival, which we cannot start now for obvious reasons, but it will happen. It is a wonderful, beautiful initiative. Tell me how you see the Pan-American music scene.

I believe the American continent offers enormous perspective and diversity. If we think of it from Canada to countries like Argentina or Chile, it is vast. As a curator, I want to make sure that diversity is shown and that we break stereotypes a bit – the culture of Argentina is not the same as it is in Colombia or Venezuela or Mexico, but at the same time, we have many things in common. In Europe, they have a wonderful tradition, but it is a tradition with a long history. In America, there is a freshness.

Being connected through diversity is the spirit of our culture. I love it because the moment we do concerts again, we will start with this wonderful festival enriched with all of your knowledge and love for this music.

And my love of the Los Angeles Philharmonic community. I have always said that the orchestra and your vision, Gustavo, is a community vision. I love that the orchestra is seeing its surroundings. It is seeing its city, which is a community with enormous diversity and multiculturalism.

The orchestra has to be a reflection of its community. It has to embrace all cultures because that is the beauty of what we do. We build bridges and that is what enriches us as humans and nourishes the art that we make.

Listen Up

A Playlist by Gabriela Ortiz

If it weren’t for the small matter of a global pandemic, composer Gabriela Ortiz would have been a frequent visitor to Los Angeles this fall as the guest curator of the Pan-American Music Initiative’s (PAMI) inaugural year. The five-year LA Phil initiative was created by Gustavo Dudamel to highlight the diversity and creativity of the Americas today. In conversation with Dudamel, Ortiz expressed the same desire, to break down stereotypes and transcend sonic borders. While we’ll have to wait to see Ortiz’s picks live, she’s put together a PAMI playlist that begins with the classic composers of her native Mexico, moves to the contemporary, and then broadens out to include work from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Colombia.

SEEING MUSIC WITH

JORDAN WONG

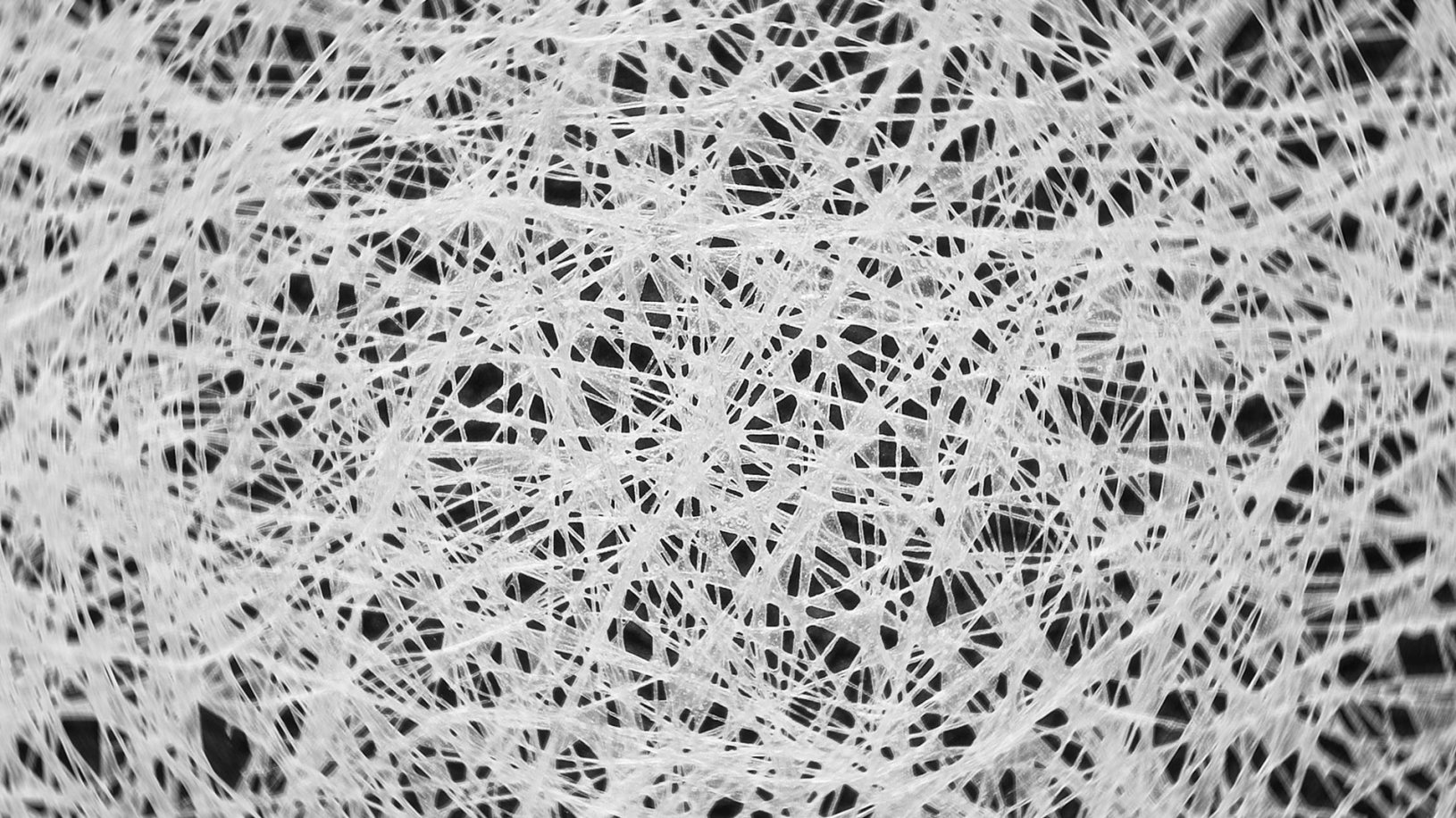

As part of Sound/Stage, the LA Phil reached out to visual artists, writers, photographers, filmmakers, and dancers to reflect on our musical programs and their themes. For classical pieces like Ravel’s Mother Goose, we reached out to experimental animators and asked them to create a piece in the spirit of the early 20th-century artist and animator Oskar Fischinger, who revolutionized motion graphics by combining synchronized abstract visuals with musical accompaniment. Experimental animator and filmmaker Jordan Wong described his approach to the assignment: “This short was created using a replacement animation technique, a process that involves analytically photographing commercially patterned fabric. When carefully rotated and intricately arranged in a particular order, certain printed textiles have the ability to come to life, especially when paired with music.”

EP 9 CREDITS An LA Phil Media Production Gustavo Dudamel Music & Artistic Director Directed by James Lees Alejandro G. Iñárritu, special guest LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC LA PHIL STAFF SOUND DESIGN Fred Vogler LIGHTING DESIGN Robin Gray Academy Lighting Consultants IATSE LOCAL 33 Kevin Brown, Master Carpenter Andy Kassan, Master Electrician Donald Quick, Property Master Michael Sheppard, Master Audio-Visual/Union Steward Kevin Wapner, Assistant Audio-Visual The stage crew is represented by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and Moving Picture Machine Operators of the United States and Canada, Local 33

The Los Angeles Philharmonic thanks the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and the Department of Parks and Recreation who value assuring access to arts and culture in Los Angeles: BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Hilda L. Solis, First District Mark Ridley-Thomas, Second District Sheila Kuehl, Third District Janice K. Hahn, Fourth District Kathryn Barger, Fifth District and Chair PARKS AND RECREATION Norma E. Garcia, Director of Parks and Recreation and Regional Parks and Open Space District EDITED AT PARALLAX Editor: Ross Constable Additional Editors: Yiqing Yu & Guangwei Du Executive Producer: Graham Zeller Post Producer: Rebecca Rose Perkins Color Correction: Bossi Baker Sound Mix: Unbridled Sound WEBSITE ToyFight