Support the LA Phil

Keep the music going. If you are able, please help the LA Phil continue to make programs like this one and impact lives through music education.

Give now:

Season 1 - EP7

Solitude

This concert’s streaming date has passed. Enjoy its accompanying essay, interview, special performances and more below.

This episode was released on Jan 1st

About the episode

The 16th-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote in his classic essay “On Solitude,” “We must take the soul back and withdraw it into itself.” Spiritual practitioners, from St. Augustine to the Buddha, would agree with him. During the pandemic, finding solitude has become a more complicated endeavor. There’s either too much or too little, but no matter your circumstances, music offers a pathway to “taking back” our souls and finding a moment of peace in a tumultuous time.

Gustavo Dudamel

Conductor

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Orchestra

Program

Dawn (U.S. premiere)

In this piece the sunrise is imagined as a constant event that moves continuously around the world. At the end of the piece we are in the full sunlight and the Dawn chorus begins. This eternal dawn is presented as a “chacony” - in the word that Purcell used some 330 years ago, a mile or two away from where I am now.

– Thomas Adès

Composed: 2020

Orchestration: 5 first violin, 5 second violin, 4 viola, 3 cello, 2 bass, 2 flute, 2 oboe, 2 clarinet, 2 bassoon, contrabassoon, 2 horn, 2 flugelhorn, 2 trombone, tuba, 3 percussion, timpani, harp, piano, upright piano

Solitude (arr. Gould)

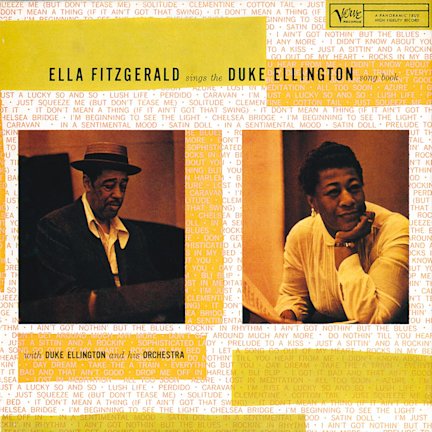

An often-written-about truism for many songwriters is that some songs take years of work and some are created in a flash of inspiration – and often it is the latter cases that are the most enduring. Edward "Duke" Ellington famously wrote “(In My) Solitude” in 20 minutes, leaning against a glass enclosure as he waited for another band to finish their recording session. Though the 1934 release of the song was labeled a foxtrot, there is unmistakable melancholy in the lyrics (added by Eddie DeLange and Irving Mills) and harmony instead of a lively dance. The jazz standard has been recorded by the likes of Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong, and the piece was later arranged for string orchestra by American composer Morton Gould.

In my solitude you haunt me With reveries of days gone by In my solitude you taunt me With memories that never die

I sit in my chair Filled with despair Nobody could be so sad With gloom ev’rywhere I sit and I stare I know that I’ll soon go mad

In my solitude I’m praying Dear Lord above Send back my love

Composed: 1934

Orchestration: 7 first violin, 6 second violin, 5 viola, 4 cello, 3 bass, harp, celesta

Solitude

By Pico Iyer

Solitude is the state in which you feel least alone. But you have to spend time by yourself to remember that. I’ve passed the last 48 hours in this silent cell in a hermitage high above the blue silences of Big Sur, and I’ve never felt so richly companioned. That rabbit scuffling through the undergrowth in my private garden, the blue jay that just alighted on my fence: They’re closer to me than my thoughts. Friends I haven’t seen for years – friends I’ll never see again – come back to me here as they never could in a crowded room. Walls disappear as soon as I engage the world in an undistracted heart-to-heart.

Why seek out solitude? Only so I can have something happy and different – fresh – to share with my friends. Otherwise I’m just sleepwalking through my days, chit-chatting about nothing. It’s only by stepping away from the world that I recall what I most love in it and how best to give back something rich and real.

These words – of course – come to you from solitude. The truest words always do. If I’m clacking away in a jampacked airport, if someone else is bustling all around me, I can’t begin to hear what’s essential. It’s only in silence that something wiser or deeper than I am has space enough to speak.

These words come to you from solitude. The truest words always do.

So, too – we all know – with the music that we love: even at its warmest and most festive, the thunder of a Beethoven symphony, the rapturous celebrations of Handel, come into being only through one soul hearing something transforming with interference from no one else.

You can respond to it best if you’re alone, too. Indeed, that’s what every exchange of music is about: by giving a piece all your being, you feel less alone than you would otherwise. Each musician with her own instrument, every audience member in his own space. Two solitudes touch and the world explodes into song.

Author Bio - Pico Iyer is the author of 15 books, most recently The Art of Stillness and two twinned books about his longtime home near Kyoto, Autumn Light and A Beginner’s Guide to Japan.

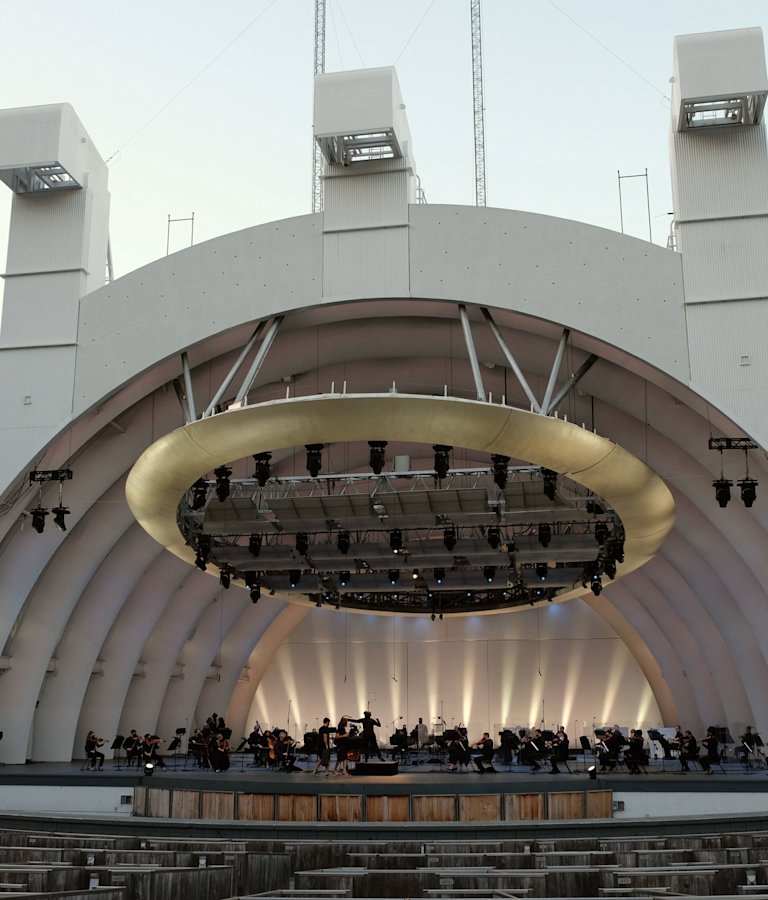

Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic take the stage for episode 7.

John Lofton takes a pause before the premiere of Thomas Adès' piece Dawn. The required orchestra was too large to fit on the stage so the brass section was placed in the front row of box seats.

Thomas Hooten, Principal Trumpet, in the box seats

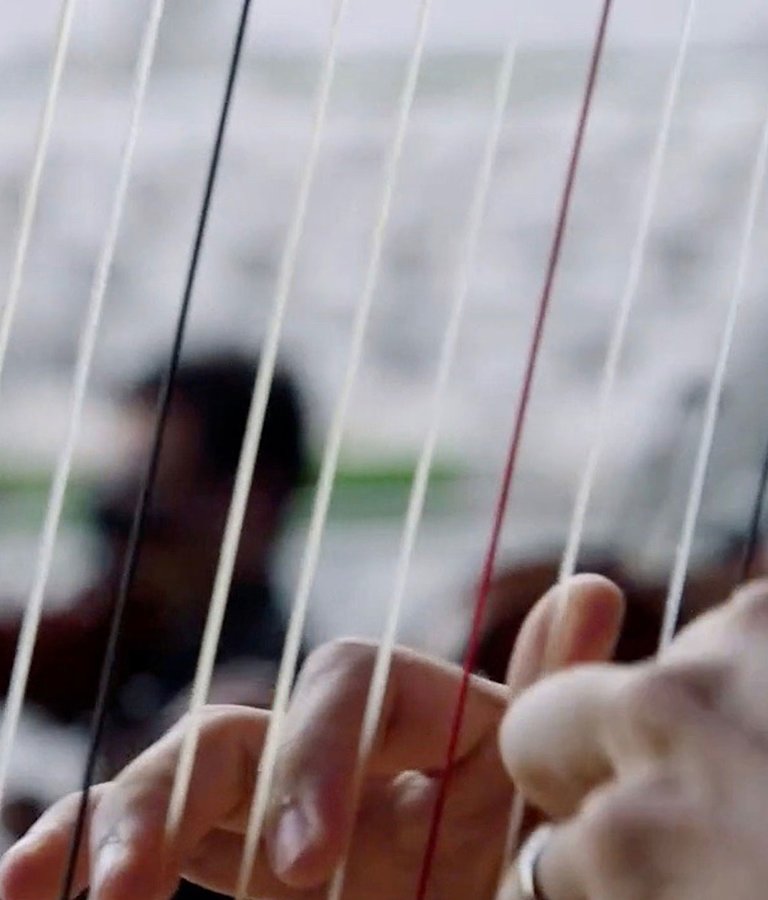

Emmanuel Ceysson, harp

Joanne Pearce Martin plays the celesta on Duke Ellington's Solitude.

Pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet performs Erik Satie's Gymnopédie No. 1 for this episode's bonus material. Watch the full performance below.

In conversation with

Herbie Hancock

In thinking about the subject of solitude, our thoughts turned to the many religious traditions that include meditation, retreats, or vows of silence. The LA Phil’s Creative Chair for Jazz Herbie Hancock has been practicing Nichiren Buddhism, which includes the chanting of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, for nearly 50 years. We sat down with Hancock to understand how seemingly solitary or internal practices can lead to a greater understanding of how interconnected and not alone we actually are.

The following has been edited for length.

You’ve been practicing Nichiren Buddhism since 1972, but you came to it through music. Would you tell us that story?

My band was playing a club up in Seattle, and there were a lot of parties after our gigs. We were young guys, right? So we went and hung out almost all night at these parties and got maybe half an hour of sleep. Then we had to get up and go to the club, and we were dragging. So we got on stage, and I took the easy way out – I chose a song that didn’t start with me. It started with the bass, and Buster Williams played bass in the band at that time.

He started with this improvisation that was astounding. I had never heard him sound like this. I mean, my jaw dropped. It was fantastic. When the band finally came in, we came in with such a force. He didn’t just wake me up. He woke up everybody in the band. We continued to play, and it was an amazing set. People ran up to the stage afterwards. Many of them were crying. Somebody reached out to shake my hand, and they said, “We didn’t just hear the music, we experienced it.” I’d never heard anybody say that, and I knew the engine for that was really Buster. So I grabbed him and took him into the musicians' room backstage. I said, “I heard you were into some new philosophy or something. Whatever it is, if it can make you play bass like that, I want to know what it is!” And that’s when he started telling me about Nichiren Buddhism, which I’ve been practicing ever since.

Can you tell us a little bit about the type of Buddhism you practice?

We believe that human beings have infinite potential. People don’t realize that. We believe that every human being is worthy of respect, even if they don’t know it themselves. The deepest part of every person’s being is their greater self. Most of what we show is our lesser self, because we’re just not aware of the power that exists inside of us and the amazing connection we have to the universe. That’s what Buddhahood is. Everybody is born with the conditions of Buddhahood manifesting. It takes continual work to arrive there, a lifetime, but everything gets better. That doesn’t mean that you won’t experience suffering and disappointment and all the other things that are part of our humanity. It doesn’t mean we won’t make mistakes, but the main thing is to be better today than you were yesterday, because there’s only this moment. It’s the only one that exists, and this moment contains the past and what we do today determines what the future is going to be when we get there.

How did practicing Buddhism change your relationship to music?

When I started playing piano, I was seven years old. I’ve been playing all my life, and I guess it’s natural that I always thought, “I’m a musician.” That’s something I’ve always been proud of. One day, while I was chanting, I started thinking about my family. I realized that to my daughter, I’m a father. Yes, I’m a musician, but that’s not the way she looks at me. To my wife, I’m a husband. To my parents, I’m a son. I’m a neighbor. I’m an American. I’m African American. I’m a global citizen. There are so many different aspects of who we all are, but the one thing that brings it all together is the fact that I’m a human being.

I had that epiphany in the eighties, and it was so profound for me that it changed the way I looked at music. It changed the way I listen to music. From that point on, when I thought about my own musical output, I started thinking not in terms of “what kind of bass line” or about the chord structure. I began to think about purpose. Why do I want to do this? What is it that I want to say to people? What is it that I want to encourage in them? This made a huge difference in how I approach making an album, making songs, the way I look at life. It’s something more fundamental. It’s a lot more important than just thinking in terms of notes and harmony and basslines. It’s life-changing stuff. Practicing Buddhism, these eye-opening experiences and realizations happen from time to time.

If you have a certain sense of your life and its purpose, it doesn’t matter what role you’re playing. It doesn’t matter the circumstances around you – you still have this forward motion and sense of yourself in relationship to others.

Right, I believe that everybody is important, and I’m important too, because as human beings, we have so much to offer every other human being. We have so much to offer in our sense of gratitude to other human beings, gratitude for being alive. I think of human beings as being part of a great earth orchestra, and each one has their own instrument that they play. There’s this great symphony we have the capacity to create. Buddhism teaches you that. There’s just so many positive things out of there. It makes you look forward to every day, no matter whether it’s rain or shine, you still look forward to it.

That’s a sentiment you shared in a letter that you and Wayne Shorter wrote to students a few years ago – how to maintain this optimism and faith in others even during our darkest hours, and right now, we appear to be in one of our darkest hours.

This pandemic is horrible. People are dying all over the planet, especially here in America, and I don’t want these people to have died in vain. One of the other ways to look at the pandemic is that it’s showing us that we are a species. It doesn’t care what your religion is, what your sexual preference is. If you’re human, you’re susceptible to it. In order to fight it, we need to work together in order to come to conclusions that will serve everyone, not just the people in our neighborhood or who were raised in our country.

We need to be together on this because we have another problem – the environmental question. We need to be together to solve that. And look at the Black Lives Matters movement – it’s been around for several years. How is it that all of sudden during this pandemic, we’re seeing people of all races – Brown people, indigenous people, Asian people – people from all walks of life, all religions joining in? We are moving toward solving something that’s existed in this country for 400 years, and people are asking questions. The same thing is happening in New Zealand and Australia with Aboriginal peoples. We’re not able to go to work, so a lot of young people are home and have the time to be able to go out in the street and to protest.

It's also about something you were talking about earlier as well. The pandemic reminds us not only that we’re a species but that we are also bound up with one another – a deeply interconnected system. I’ve never experienced anything in my entire life that I knew every other person on this entire planet was experiencing at the same time – our interconnectedness has never been so apparent.

That’s true – it’s amazing – that’s something we share. If something positive can come out of this, then those whose lives have been lost will not have been lost in vain. That’s what I want to see, and then, it’s up to us to create the kind of future that’s going to be positive for everyone.

Listen Up

A Playlist by Thomas Adès

You can tell when someone has made a playlist with the careful consideration it deserves. The opener is perfect. The order matters. You can’t imagine taking a song out or slipping another one in. And then there are the particulars: “the original album version please, not the remaster.” Composer Thomas Adès has gifted us with a perfect playlist on the subject of solitude, a subject not confined to any one genre. Classical and opera to be sure, but also Brazilian giant Caetano Veloso, influential art rocker Kate Bush, cabaret sophisticate and playwright Noël Coward, and an ending too good to spoil.

IN PERFORMANCE

Jean-Yves Thibaudet

Pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet plays fellow Frenchman Erik Satie’s most recognizable work, the elegant and melancholic Gymnopédie No. 1, from the set of three. This peaceful music has been performed in many contexts by a huge range of performers, but there’s nothing like hearing the original in its purest form.

EP 7 CREDITS

An LA Phil Media Production Gustavo Dudamel Music & Artistic Director Directed by James Lees LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC LA PHIL STAFF SOUND DESIGN Fred Vogler LIGHTING DESIGN Robin Gray Academy Lighting Consultants IATSE LOCAL 33 Kevin Brown, Master Carpenter Andy Kassan, Master Electrician Donald Quick, Property Master Michael Sheppard, Master Audio-Visual/Union Steward Kevin Wapner, Assistant Audio-Visual The stage crew is represented by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and Moving Picture Machine Operators of the United States and Canada, Local 33

The Los Angeles Philharmonic thanks the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and the Department of Parks and Recreation who value assuring access to arts and culture in Los Angeles: BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Hilda L. Solis, First District Mark Ridley-Thomas, Second District Sheila Kuehl, Third District Janice K. Hahn, Fourth District Kathryn Barger, Fifth District and Chair PARKS AND RECREATION Norma E. Garcia, Director of Parks and Recreation and Regional Parks and Open Space District EDITED AT PARALLAX Editor: Yiqing Yu Additional Editor: Guangwei Du Executive Producer: Graham Zeller Post Producer: Rebecca Rose Perkins Color Correction: Bossi Baker Sound Mix: Unbridled Sound WEBSITE ToyFight